Kind of the opposite of a day in the countryside of Berlin is a day visiting the Jewish Museum. For those of you following this journal you might have noticed that the page title has some new information: the date I posted this entry, and the date I actually visited the museum. It has taken almost 4 weeks to make this post because, well, it's just not easy to do. It's not light, it's not fun, it's not sight-seeing in the normal sense, it's not humorous. It's heavy and for many reasons I don't think this post will be in ANY measure commensurate with the feelings I had on this day. It will certainly not reflect the depth of the subject matter of the museum. What I'll try to do is give some idea of what my experience was. I encourage anyone who gets a chance to go and have your own experience in this incredible place. I don't have all that many photos, mostly because I wanted to concentrate on the experience. Again, I encourage you to do the same if you can.

This photo above is of the exterior of Daniel Libeskind's addition to the existing Jewish Museum. What I like about the picture is its justaposition with a "normal" building in Berlin. To say Libeskind's work makes a statement seems pretty obvious here. It is NOT normal. The exterior shows it, but inside you feel it. I don't want to give "spoilers" to those who will experience it in the future, but once inside, once in the courtyard, there was not a moment when I felt like I had my balance, my bearings, my orientation. Everything was "off."

The extension to the museum is laid out in three axes. At the end of one of these, up a steep ramp, is a very heavy door, leading to a room I would guess is over 100 feet high. Following the floor to the far corner of the room leads to total darkness. Above is light, completely inaccessible. The concrete walls are thick. No sound. Holes in the walls make me think of pipes for killing gas, though I tell myself they are only structural features becuase I've seen them in other places around the building. I want out. I know I can get out. I stay, and feel what this place feels like. When I leave, it is not exactly a relief. I carry something with me.

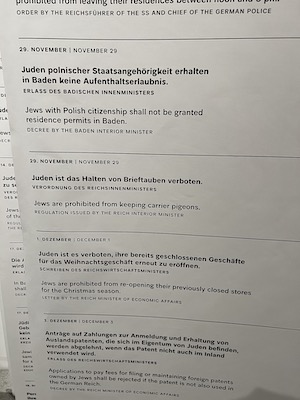

One of the many things I admired about the museum was the variety of exhibitions. The architecture is spectacular and visceral; other exhibitions were more cerebral. Here are a couple of pictures of an exhibition about the laws passed against Jews during the years of Nazi government. The first photo shows one of the three walls absolutely full of floor to ceiling lists of laws passed throughout Germany over the 12 years. Most were passed early on, making it not only difficult or impossible for Jews to work but also to leave the country. The next photo is a tiny fragment of those laws. I was particularly struck by the apparently absurd item prohibiting the possession of carrier pigeons. But something struck me there.

The exhibition, "Shaleket (Fallen Leaves)" by Manashe Kadishman features more than 10,000 faces cut into heavy iron disks. These can be viewed from up much higher, or at closer range as you see here. The installation is dedicated "to the victims of war," and though this is the Jewish museum, though six million Jews were murdered in the second world war, and though the power of this exhibition is clearly related to and felt in conjunction with the Holocaust, the dedication does not end its scope of victims there.

I was surprised that people were allowed to walk on the exhibition. Actually, I was shocked. It took me a very long time to work up the nerve to do it, even though I saw, and heard, others walking. If I could figure out how to show video here you could hear the sounds. What sounds do you think walking on heavy iron faces would produce? Clanking? Right, like the sounds of iron prison door shutting. But screaming, crying? Another difficult experience, as maybe you can judge by the second picture of Monika and the rusted faces in the alcove.

One of my favorite exhibitions - probably because it was a little lighter - was a series of videos of contemporary day Jewish people and Rabbis discussing topics of daily life and moral dilemmas we all face. I loved that there were about as many views on what constitutes proper Shabbat, say, as there were people portrayed in the videos. Humor, pathos, regret, encouragement, vitality, hope. These, among many more feelings were reflected in the exhibition, and made for a nice return back out into the day, with its retuned and a bit fractured architecture.

Maybe, though probably not, a final thought on my experience here. Apparently, it's not all that difficult for human beings to be completely inhumane. It's not that difficult to be just completely fucked up to ourselves, each other, and to the world in which we all live. Fear is not new. Anger is not new. And the manipulation of fear and anger and hatred in the "service" of some "cause" has created our worst moments. The reminders of one of the horrors of the Holocaust are all over Germany and Berlin in particular. But in many ways these feel transient and almost superficial in the face of the magnitude of the ancient tribalisms and hatred and ignorance I can see in America today and really in so many of the authoritarian regimes in place all over the world. On the anniversary of the book burnings in Berlin, I wonder how far off these things are in, say, Florida, or anywhere else. True justice in the rule of law is certainly not an immutable thing. I'm reading a pretty good book: "Learning from the Germans: Confronting Race and the Memory of Evil" because I've become interested in the changes, both physical and social, in Germany since WWII. This book suggests that there may be some lessons for America and its legacy of slavery. Hmmm. Let's see what comes of this...